“For too long our light has been refracted through other people’s prisms.”

—Leslie Feinberg, Transgender Warriors

The biopic — or film biography — is a bellwether of a highly individualistic culture’s priorities. Biopics teach audiences what real people are worth giving time, money, energy, and attention to, and as such, they matter. “The genre’s charge”, Dennis Bingham writes, “is to enter the biographical subject into the pantheon of cultural mythology, one way or another, and to show why he or she belongs there.” This cultural mythology is important, and it’s worth examining when and in what contexts trans subjects have been allowed in — or denied entry.

While the biopic is not the only point of entry, the biopic is, within American culture, perhaps the most vaunted point of entry; George Custen has suggested that “most viewers, at least in part, see history through the lens of the film biography” (2). And in the midst of what Ellen Cheshire describes as a revitalization of the genre in recent years, the biopic has obvious relevance for how we do, or perhaps more importantly do not, tell stories about the world.

In his book Whose Lives Are They Anyway?, Bingham argues convincingly that biopics comprise their own distinct film genre. And if, as Bingham suggests, male and female biopics are so different as to constitute “essentially different genres”, then I would argue the same is true of the transgender biopic. Although the transgender biopic as it appears here bears a great deal of resemblance to Bingham’s analysis of the female biopic — perhaps because all but two of the films discussed feature transfeminine subjects, perhaps because women and trans people each occupy, relative to men, marginalized social positions — the transgender biopic has enough distinct features to place it in a class of its own.

The iconography of the classical biopic, as it has been built and theorized around cisgender figures, is uniquely suited to fitting trans people into a particularly singular narrative. In fact, the narrative conventions of the biopic have a great deal in common with the standard transition narrative that surrounds trans people. Meanwhile, the biopic as a form has, in its American incarnations, been used at cross-purpose with its own mission not to elevate but to avoid elevating transgender figures and reinforce the trans community’s subaltern status.

Trans biopics are what Tourmaline, Eric A. Stanley, and Johanna Burton, editors of Trap Door: Trans Cultural Production and the Politics of Visibility, describe as “‘doors’—entrances to visibility, to resources, to recognition, and to understanding” which “are almost always also ‘traps’—accommodating trans bodies, histories, and culture only insofar as they can be forced to hew to hegemonic modalities” (xxiii). The biopic offers what appears to be an entrance into cultural mythology while the films ultimately perform the opposite task by reducing trans people to a standardized narrative trajectory.

With the biopic’s strong ties to classical Hollywood cinema and its creation of a particular white, heterosexual, cisgender cultural mythology — as “one of the most conservative genres in cinema”, according to B. Ruby Rich — the biopic has been ill-suited to subcultural mythologizing. Bingham questions “whether it is actually possible for a filmmaker and subject matter that historically were marginalized to take up the classically celebratory majoritarian form without being assimilated by it”; this is worth keeping in mind as we discuss how the biopic has traditionally imaged trans figures and how the form might be repurposed.

The biopic as hegemonic form not only begs the question of how trans people have been denied entry into certain cultural mythologies — particularly white, cisgender mythologies — but whether such entry is desirable when trans communities have, by necessity, created their own. It is worth questioning whether mainstream forms of recognition — individualism, hierarchization, commodification — through the biopic are even desirable in the first place.

In that regard, the purpose of this article is not to decry “negative representation” or demand “positive representation” within the scope of the biopic, but rather to interrogate how one way of telling history has figured trans images and what that means for how trans communities might tell their own histories. Meanwhile, the flaws inherent in visibility — a prominent feature of the biopic of the marginalized person — are a key theme throughout the Trap Door anthology: for example, micha cárdenas writes that “[m]ainstream trans visibility today is put in the service of selling magazines, video streaming services, and web advertising impressions and clicks in order to erase the anticolonial struggles and histories of struggle of trans people of color” (172).

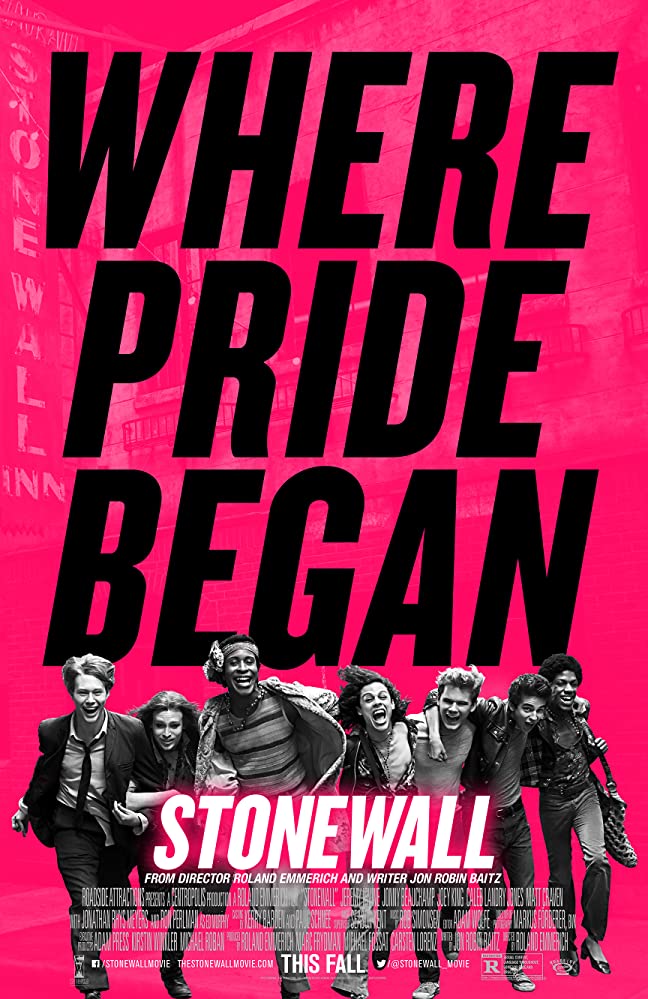

In an era where Pride has come to signify corporate sponsorships and police partnerships, the recent film Stonewall‘s tagline “Where Pride Began” becomes little more than a dogwhistle for the very assimilationist politics the film pretends to oppose. Thus the mainstream biopic of a member of a marginalized group must be seen in the light of the potential flaws and limitations of visibility.

The classical biopic, especially of the cis, white, male subject, goes through a series of motions to enact the subject’s entrance into that cultural mythology: the subject must contribute something to society to be worth retelling; the subject must face opposition from that same society (or parts of it) who fail to realize the subject’s genius or talent; the subject overcomes opposition and has their greatness realized.

The trans biopic subject, by contrast, is typically bogged down in the details of transition itself, leaving little room for accomplishment outside of simply being trans. While the typical biopic follows a subject through to their most notable accomplishments, the trans biopic subject essentially only lives the first act of a typical biopic: they become the person they need to be (or in the case of the second wave, suffer violence before that can happen), and then the film is largely over. This, though, is largely the point: to deny trans lives meaning and even existence outside the scope of transition itself.

To begin, let’s take a look at a film that speaks to the role trans people play in the larger cultural imaginary.

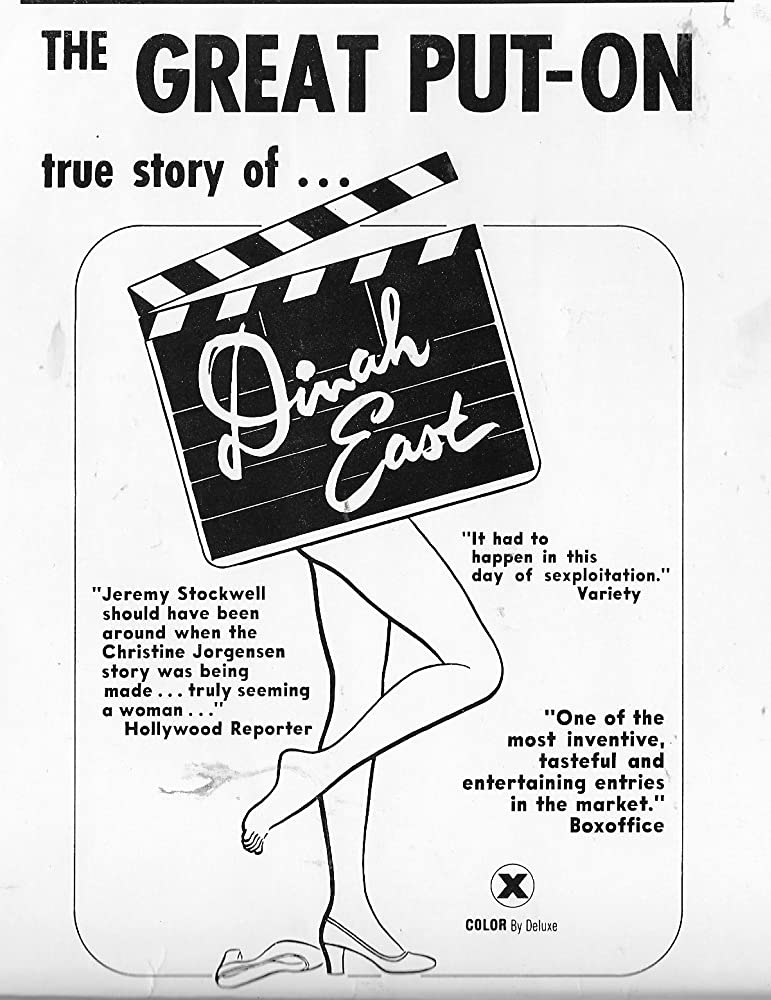

Dinah East (1970)

Where trans people are so frequently erased from cultural narratives, one film performs the reverse by inserting a trans woman where ostensibly one does not exist (as Ron Woodroof biopic Dallas Buyers Club included the fictional Rayon). Dinah East is an alternate-reality biopic which extrapolates the rumor that Mae West was assigned male at birth (Hamilton 235). The same point had been made in Michael Sarne’s fantastic Gore Vidal adaptation Myra Breckinridge (1970), which cast West alongside Raquel Welch’s titular transsexual (Hamilton 235), but Dinah East operates squarely on the conventions of the biopic.

via IMDb

Structured like Citizen Kane, the film begins with Dinah’s death and derives most of its content from the memories of those who knew the title character. In doing so, Dinah herself is denied a voice and she becomes mythologized, the ultimate transgender biopic subject: both unreal and hyper-real at once, a sensational death-object for examination by cisgender characters. As a film based in the bizarre, hidden corners of a more mainstream-oriented transgender mythology, Dinah East speaks to the exploitative fascinations surrounding trans people’s very existence in a world not built for them.

I begin by discussing Dinah East because despite not being a true biopic, the film has a lot to tell us. It is in fact because of the film’s fictional status that it can help reveal the operation of the transgender biopic as a genre that transforms the trans subject into object of cultural fascination. Dinah East is the rare trans biopic that doesn’t follow the trajectory to follow, but in so doing it becomes the exception that proves the rule, suggesting that alternative temporalities are available only in fantasy. The speculation about Mae West’s secret trans-ness that informs this film also illustrates that while trans-ness itself is ripe for the mainstream imagination, actual trans people are more or less irrelevant. In essence, the trans biopic doesn’t care much about who their subject was except that they are trans.

In selecting the films described here, I have taken my basic criteria — that the film is about a real-life trans person and makes some claim to reality — and allowed the discussion to radiate from there to touch films like the aforementioned Dinah East (obviously not about a real trans person) and, later, Roland Emmerich’s Stonewall (not centered on the trans people in the film). I have, in spite of this, limited myself to trans people as starring rather than supporting characters.

There is a variety of trans people (both real and fictional) in biopics — the fictional Rayon in Dallas Buyers Club and the real-life Candy Darling in I Shot Andy Warhol, to name two — but they fall outside the scope of discussion here. It has not been my intent to be exhaustive, and I have certainly made omissions. My goal is to capture the essence of what the trans biopic has meant, particularly in the context of biopics made by cis people about trans people. And to capture that, I look at films indicative of the two major waves of classical trans biopic.

Glen or Glenda (1953)

I Was a Man (1967)

The Christine Jorgensen Story (1970)

Second Serve (1986)

Glen or Glenda inaugurates the trans biopic (as it inaugurates so much of transgender cinema) by rushing to the screen a loose adaptation of Christine Jorgensen’s life story along with that of its own director, Edward D. Wood, Jr., according to Rudolph Grey’s Nightmare of Ecstasy (Wood eventually got his own biopic in the form of Ed Wood, based on Grey’s book). The Jorgensen figure is a static, medicalized figure, essentially a walking sexology lecture, which is fitting, given that the story is framed as a sexologist lecturing a police inspector.

Similarly, I Was a Man (released the same year as Christine Jorgensen’s biography) opens on a doctor setting up what we’re about to see. The Christine Jorgensen Story, while free of a medical framework for the story, nonetheless places great emphasis on the mechanics of transition, a strategy repeated later by The Danish Girl. These films essentially open up the machinery of transition to reveal the engines of change and end as that change is seen as complete.

In the case of The Christine Jorgensen Story, that involves abruptly cutting the narrative off through narration by a journalist, while in Glen or Glenda this involves Anne’s adoption of acceptably feminine traits and her reintegration into society as a “proper” woman. Second Serve, which I have been unable to locate in full, may be an exception, although apparently only “the last third”, according to reviewer John J. O’Connor, involves Renée Richards’ attempts to play professional tennis as a woman. At least she reaches some sort of accomplishment.

One of the functions of the biopic, as described by Bingham, is “for both artist and spectator to discover what it would be like to be this person, or to be a certain type of person”. The latter is the dominant function of the early examples of transgender biopic: to understand a particular “type of person”. But though Bingham lists it as a primary function of the biopic (without ever exploring the concept further), exploring type fundamentally conflicts with the biopic’s mission of singling out individuals who usually transcend type; the genre is, as B. Ruby Rich suggests, “tied to the fabled exceptionalism of the single heroic (or pathological) individual” (249).

This is what makes the transgender biopic a contradiction: in the two waves of classical transgender biopic, the transgender individual is almost always reduced to some extent to a type. A genre designed to single out and elevate (or lower) individuals, when it comes to trans people, often does the opposite. Hence the exclusion of transgender imagery from the iconography of the classical biopic and the need to understand trans biopics as their own category.

Where the classical biopic subject does something — sport, invention, politics — becoming is what the trans biopic subject frequently does. Ellen Cheshire’s book Bio-Pics groups biopics by the subject’s field of activity, and this, again, leads to a scenario in which the trans biopic stands distinct. I Was A Man, The Christine Jorgensen Story, Second Serve, A Girl Like Me, and The Danish Girl and the Anne segment of Glen or Glenda are very prominently transition narratives.

But in contrast to the biopic, there really is no way to excel at being trans, to excel at transitioning, except to serve as a representative example. The trans person is made into a type to exemplify what trans people are, not what trans people have done or accomplished. This is especially true when, as is pronounced in The Christine Jorgensen Story, The Danish Girl, and Glen or Glenda, transition is something done to trans people by doctors, not done by the trans people themselves.

George Custen’s 1992 book Bio/Pics cites Renée Richards biopic Second Serve alongside a discussion of the fact that “[n]otoriety has, in a sense, replaced noteworthiness as the proper frame for biography; short-lived, soft news has replaced the harder stuff, history” (216). Renée Richards is implicitly deemed unworthy of a “hard” (read: legitimate) biographical treatment. In a book subtitled How Hollywood Constructed Public History, Custen is doing his own part to construct history as something which clearly doesn’t belong to trans people.

These biopics contribute to this perception by focusing their efforts on trans people as medical curiosities, de-historicizing them as though they do belong only to the astonishing present or even some kind of science fiction future. Even Jorgensen’s biopic proper, The Christine Jorgensen Story, utterly ignores Jorgensen’s post-transition life or the socio-political ramifications of her coming out except in the final lines of the film, which A) pretend/imagine that the culmination of the trans movement is the ability to have bottom surgery performed in the United States, and B) lock Jorgensen out of the moment by having someone else narrate it. Decades later The Danish Girl, truly the reincarnation of The Christine Jorgensen Story, will similarly feature a post-script blandly connecting Lili Elbe to the modern trans movement.

Boys Don’t Cry (1999)

Soldier’s Girl (2003)

A Girl Like Me: The Gwen Araujo Story (2006)

Bingham writes that “[b]iopics of women … are weighted down by myths of suffering, victimization, and failure by a culture whose films reveal an acute fear of women in the public realm”. The same, I would argue, is true of transgender biopics, particularly at the turn of the millennium and beyond. While suffering and victimization mark trans people in Glen Or Glenda, I Was A Man, The Christine Jorgensen Story, and Second Serve, the degree and weight of tragedy is amplified in the second wave of biopics that appeared in the late 1990’s and 2000’s, three films that deal with the deadly consequences of transphobia: the murders of trans man Brandon Teena (Boys Don’t Cry), teenage trans girl Gwen Araujo (A Girl Like Me: The Gwen Araujo Story), and Barry Winchell, who was in a relationship with trans woman Calpernia Addams (Soldier’s Girl).

Unlike The Christine Jorgensen Story and Second Serve, these three films showcase trans people who were unknown publicly until tragedy struck, tragedy each film connects to the trans status of its characters. And despite the usually liberal, ostensibly positive angle taken by these films, they nonetheless reveal a process by which the trans characters are consumed both by the societies that in real life took transphobia and homophobia to its deadly extremes and by films (and audiences) that are more interested in trans corpses than trans lives, representing, to use Bingham’s phrase, “victimology-fetish” biopic.

If the first wave of trans biopics was guilty of stripping trans people of their historical and cultural context, the next wave solves that problem… sort of. Boys Don’t Cry, A Girl Like Me, and Soldier’s Girl use violence based in transphobia as, once again, a representative example — whether implicitly (as in Soldier’s Girl), very explicitly (as in A Girl Like Me) or somewhere in between (as in Boys Don’t Cry) of violence against other trans people.

But this still means trans characters become representative examples, standing in for themselves and other trans people in a broad social context. I’ve been over this before in “Methodical Killing” regarding film and television’s large transgender body count, and it bears repeating here: the repeated retelling of transphobic violence is necessary, but when it occurs in isolation, and especially when it is fictionalized, it becomes self-defeating. This trio of films suggests that trans people are often only worth mythologizing after death.

Ed Wood (1994)

Tim Burton’s excellent Edward D. Wood, Jr. biopic is something of an outlier in that Ed Wood is a biopic of a person on the transgender spectrum that focuses more on his accomplishments than his gender variance, to say nothing of fairness to an artist unfairly maligned as “worst” — most famously by the Medveds, whose book The Golden Turkey Awards awarded Wood the Worst Director title and Plan 9 From Outer Space the Worst Film title.

As Ellen Cheshire notes, “[t]he film’s original title, The Man in the Angora Sweater, drew attention to Wood’s transvestism” (38); in renaming the film, the filmmakers decenter Wood’s gender variance and highlight his trash auteur status instead. That said, even once the film moves beyond the filming of Glen or Glenda, Wood’s cross-dressing will be crucial to the resolution of the narrative, as he dons a skirt, a wig, and an angora sweater in order to direct Plan 9 From Outer Space, thus tying Wood’s gender non-conformity to his ability to make the art for which he would be known. Thus Ed Wood is the rare film that makes trans status a source of power that feeds into a transgender person’s accomplishments, as opposed to being trans being an accomplishment in itself.

At the same time, Ed Wood throws the hyper-narrativization of trans people into stark relief. Like Dinah East, Ed Wood is an exception that proves the rule: as a cross-dresser, Wood’s gender variance can be contained within a larger narrative. People who, unlike Wood, strive to live in entirely different genders — as in the subjects of films discussed above — are more strongly pushed into pre-made narrative trajectories built around transition as a journey from point A to point Z (a journey that is tragically and violently arrested in films like Boys Don’t Cry and A Girl Like Me).

The trans biopic is bogged down by, to use Elizabeth Freeman’s term, “chrononormavity”: the hyperlinear sense of time that forces trans people into recognizable narratives with beginnings, middles, and ends. Jack Halberstam’s point that “queer temporality disrupts the normative narratives of time” suggests that the chronological transition narratives of the trans biopic and elsewhere need not be the only way to shape transgender stories.

If Ed Wood shows us anything, it is that the biopic is not technically incapable of telling trans spectrum stories with some balance, while at the same time it reveals the reasons and the ways that the classical biopic has bent trans stories to its own pre-cut narrative trajectories. And nothing exemplifies this more than the next two films on the list.

The Danish Girl (2015)

Stonewall (2015)

Tom Hooper’s lavish film The Danish Girl, which dramatizes the life of Lili Elbe, synthesizes the two waves of transgender biopic noted above. Like The Christine Jorgensen Story (and fictional contemporaries such as I Want What I Want), The Danish Girl is sharply focused on the details of transition. In a film obsessed with surfaces and textures, and with cisgender Eddie Redmayne playing Elbe, the film’s central character becomes just one more surface, like paint on a canvas. Like Boys Don’t Cry, the film is also preoccupied with tragedy as an advocacy strategy, generating sympathy for Elbe through violence enacted on her and through her untimely death. As a frustrating amalgam of the worst of each wave of biopic, The Danish Girl illustrates that neither trend is entirely extinct.

The production of Roland Emmerich’s Stonewall signals a heightened awareness, or a desire for a heightened awareness, of one of the more significant events of queer history. Any film called Stonewall probably should not be a biopic but rather an decentralized ensemble film, such as the approach taken by Ava DuVernay’s Selma, but Emmerich plays his film as a biopic, focusing the action on a single character whose life is charted before and after the climactic events in which he plays the most instrumental role.

The film’s basic structure is exactly that of the 1995 film Stonewall, part of the wave of pop drag films of the mid-90’s (including The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert, To Wong Foo, Thanks For Everything, Julie Newmar, and The Birdcage). Both films feature a fictional cis, white gay man who comes to New York from the Midwest. In both films, said character gets caught up in a highly symbolic conflict between Greenwich Village street queens and the more straight-laced middle- and upper-middle-class cis gay men representative of different strategies of activism: a forceful, rebellious approach or a polite, restrained legal approach.

In each film, the Stonewall riots begin when the protagonist makes his choice in the conflict, making him symbolically (and in Emmerich’s film, literally) the spark that lights the revolutionary fire. In centering a fictional white, cis man, Emmerich participates in the ongoing erasure of the central role that trans women of color like Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera played at the event. At the same time, by structuring the film as a biopic, Emmerich participates in the deeply problematic individualization of history, a history made by far more than a single person.

Or, for that matter, a single event. Grace Dunham points out that

on that evening in June of 1969, no one present narrated the [Stonewall] riot as the beginning of the modern gay rights movement; this narration has shifted and been catalyzed by a mainstream, state-sanctioned gay agenda that seeks to absorb the riots into its narrative of progress (93).

This is crucial because those same Big Gay progress narratives into which Stonewall has been assimilated tie in closely to the trajectory of the classical biopic and to the trajectory of the classical transition narrative. Although Rita Felski points out that for many theorists, “the destabilization of the male/female divide is seen to bring with it a waning of temporality, teleology, and grand narrative”, trans identities are perhaps more than any other forced into just such “grand narratives”.

Felski continues: “the end of sex echoes and affirms the end of history, defined as the pathological legacy and symptom of the trajectory of Western modernity”. But it is this very trajectory that trans identities, through the biopic, are worked into. Trans people are made into history incarnate, what Dunham calls a “narrative of progress”, a narrative of beginning to end — after which the trans film subject ceases to meaningfully exist — that serves neoliberal interests, including the assimilation of queer and trans lives into logics of global capitalism.

Emmerich’s film not only buys into the erasure of previous moments of resistance (such as those at Compton’s Cafeteria and Cooper’s Donuts [Dunham 93; Stryker 59-75]) but also denies a more open and less fixed temporality (or multiplicity of temporalities) that allows trans narratives to go beyond what is expected. The same way that trans figures are so often trapped within the ultra-linear transition narrative, Emmerich makes Stonewall into the beginning of a particular cultural narrative that typically ends with Obergefell v Hodges, the U.S. Supreme Court decision legalizing same-sex marriage.

Stonewall is thus an apologia for the Obergefell decision as the climax of the queer movement, while The Danish Girl is yet another film demanding that trans lives fit the contours of both the biopic and the transition narrative, ending as Lili Elbe dies, with the epigraph positioning the modern day as the “end” to Lili Elbe’s beginning, again foreclosing more radical futures or timelines.

Morgan M. Page, creator of the transgender history podcast One from the Vaults, makes the point that “our current cultural moment—the so-called transgender tipping point—is not the panacea we’re told it is. Drowning in a sea of media and legislative visibility, we’ve been sold the lie that visibility and ‘awareness’ will save us” (142). Indeed, films like The Danish Girl and Stonewall are indicative of the false promise of visibility and awareness, especially when that awareness largely originates with cisgender speakers. By framing the histories of One from the Vaults as “gossip”, Page does her part in, as she puts it, “breaking open the archive” (137) that has been put in place by formalized and institutionalized modes of history.

The biopic falls somewhere in the middle of these modalities. As a genre, it is more accessible to more people than most scholarly or academic historical work. Indeed, at times the trans biopic can seem a lot like gossip: scandalous, lively, and organized around recognizable narrative forms. But at the same time, the biopic has never been a form of grassroots storytelling, restricted not in the sense of who is allowed to view it but in who is allowed to tell it. It is telling that in the wake of the 2014 declaration of “The Transgender Tipping Point” — the title of Katy Steinmetz’s now-(in)famous Time story, which appeared on the cover alongside a photo of Laverne Cox — a major biopic was produced about a trans woman frequently referred to as the first trans person to medically transition.

In Page’s words, “we’ve been here before” (142): Neils Hoyer’s book Man into Woman — which also tells Elbe’s story and which was partly the basis for both the book and film The Danish Girl — was notably reprinted as a paperback following Jorgensen’s much-publicized coming out in late 1952 (Stryker 77). Mainstream history fixates on (often fabricated or exaggerated) points of origin, and as a consequence, the messiness of history and the full vibrance of trans history are often ignored in favor of simplified narratives that tend to favor white, abled, and middle- and upper-class trans people who are stuck in a cohesive narrative, foreclosing the possibility of unruly futures. When the fascination somehow shifts from points of origin, it shifts to end points, death and trauma, that similarly foreclose the possibility of futures.

“Happy Birthday, Marsha!” (2018)

But perhaps the biopic as a form is not incapable of telling trans histories after all. “Happy Birthday Marsha!”, directed by Tourmaline and Sasha Wortzel and starring Mya Taylor, promises be an antidote to Stonewall. “Happy Birthday, Marsha!” is a film about Marsha P. Johnson, one of the trans women of color who was at Stonewall and whose place in queer and trans history is inestimable. I’ve yet to see the film, but notably, “Happy Birthday, Marsha!” appears to take a less classical approach, avoiding the compendium in favor of a small slice of life — focusing on “her life in the hours before she ignited the 1969 Stonewall Riots”, as the film’s synopsis says — that challenges the traditional biopic’s approach to the subject even as it reminds audiences of the need for trans histories and heroes.

In their introduction to Trap Door, editors Tourmaline, Eric A. Stanley, and Johanna Burton suggest that “the film tells a much more complex story that challenges the hierarchy of intelligible history and the archive that keeps our stories as trans and gender nonconforming people from ever surfacing in the first place” (xix). “Happy Birthday, Marsha” comes as transgender filmmaking is on the rise: beyond The Wachowskis, trans filmmakers and video artists like Sydney Freeland (Drunktown’s Finest, Her Story), Eric A. Stanley and Chris Vargas (“Homotopia”, Criminal Queers) and Zackary Drucker and Rhys Ernst (“She Gone Rogue”) are pushing the boundaries of trans visual storytelling as we see trans histories told in unconventional ways: for example, season two of Transparent (2015), which blurs the boundary between past and present while flashing back to 1933 Berlin and Magnus Hirschfeld’s Institute of Sexual Research.

And while it is heartening to see Scarlett Johansson back out of portraying trans man Dante Gill in the biopic Rub and Tug, the deeper question remains: can the biopic be salvaged for transgender people telling their own histories? Of “Happy Birthday, Marsha!”, the filmmakers say,

As queer and trans artists, we have found that oppression does not solely affect our material conditions. Our relationships with each other, our ancestors, and our communities are also at stake … We truly believe that how we tell the stories of our heroes matters.

Indeed, if the proliferation (and constant generic reinvention) of biopics tell us anything, it is that “how we tell the stories of our heroes matters”. And while there are reasons to question whether the biopic as classically constructed is a desirable mode of remembrance (if The Danish Girl is any indication, it is not), we should look to films like “Happy Birthday, Marsha!” to see how we can turn the biopic on its head and reclaim our histories.

Epilogue

This post, like many I’ve been publishing lately, was originally written a while ago. I have since had an opportunity to watch “Happy Birthday, Marsha!” (it’s on Amazon Prime), and it only affirms what I said about the film then. This piece is long enough though; please just watch the film for yourself.

Works Cited

Bingham, Dennis. Whose Lives Are They Anyway? The Biopic as Contemporary Film Genre.

cárdenas, micha. “Dark Shimmers: The Rhythm of Necropolitical Affect in Digital Media”, pp. 161 – 181 in Trap Door: Trans Cultural Production and the Politics of Visibility, edited by Reina Gossett, Eric A. Stanley, and Johanna Burton.

Cheshire, Ellen. Bio-Pics: A Life in Pictures.

Custen, George F. Bio/Pics: How Hollywood Constructed Public History.

Dunham, Grace. “Out of Obscurity: Trans Resistance, 1969-2016”, pp. 91 – 119 in Trap Door: Trans Cultural Production and the Politics of Visibility, edited by Reina Gossett, Eric A. Stanley, and Johanna Burton.

Feinberg, Leslie. Transgender Warriors: Making History from Joan of Arc to Dennis Rodman.

Felski, Rita. “Fin de siecle, Fin de sexe”

Filmmakers’ statement on “Happy Birthday, Marsha”, happybirthdaymarsha.com.

Freeman, Elizabeth. Time Binds: Queer Temporalities, Queer Histories.

Grey, Rudolph. Nightmare of Ecstasy: The Life and Art of Edward D. Wood, Jr.

Groothuis, Eleven. “Methodical Killing: Losing Trans Film Characters Devalues Them IRL”, Bitch Media.

Halberstam, Judith. In a Queer Time and Place: Transgender Bodies, Subcultural Lives.

Hamilton, Marybeth. When I’m Bad, I’m Better: Mae West, Sex, and American Entertainment.

Han, Karen. “Scarlett Johansson backs out of playing a transgender man after backlash”, vox.com, July 13, 2018

Medved, Harry, and Michael Medved. The Golden Turkey Awards: Nominees and Winners— The Worst Achievements in Hollywood History.

O’Connor, John J. “CBS’S ‘SECOND SERVE'”, The New York Times, May 13, 1986.

Page, Morgan M. “One from the Vaults: Gossip, Access, and Trans History-Telling”, pp. 135 – 146 in Trap Door: Trans Cultural Production and the Politics of Visibility, edited by Reina Gossett, Eric A. Stanley, and Johanna Burton.

Rich, B. Ruby. New Queer Cinema: The Director’s Cut.

Stryker, Susan. Queer Pulp: Perverted Passions from the Golden Age of the Paperback.

———. Transgender History.

Tourmaline, Eric A. Stanley, and Johanna Burton. “Known Unknowns: An Introduction to Trap Door“, pp. xv – xxvi in Trap Door: Trans Cultural Production and the Politics of Visibility, edited by Tourmaline, Eric A. Stanley, and Johanna Burton.

- Media Literacy Means Knowing Matt Walsh is a Mass Murderer - November 22, 2022

- Quarry and Archive - October 13, 2022

- Thoughts on ‘The People’s Joker’ - September 19, 2022